How Do Clinical Trials Work?

DECEMBER 01

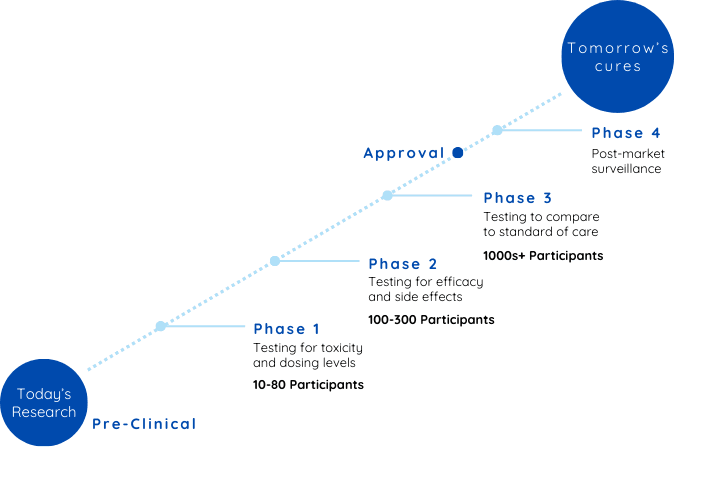

Clinical trials are the essential bridge between innovative research and the life-changing treatments available in healthcare today. Before approval, new treatments typically progress through three clinical trial phases, with a fourth phase conducted post-approval to monitor long-term safety and effectiveness in broader populations. These studies can vary widely in their design and purpose, depending on whether they are interventional or observational. Interventional trials actively test specific treatments or interventions by assigning participants to treatment groups, while observational trials focus on monitoring participants in real-world settings without altering their care. The structure and expectations of a clinical trial depend on these distinctions, guiding how researchers design the study and the types of data they collect.

By Maria Garzon

Regardless of the clinical trial type, every trial follows a structured phased approach, serving as stepping stones to deepen researchers' understanding of a treatment's safety, function, and potential to enhance lives.

But what exactly happens during clinical trials, and what can participants expect at each stage? Let’s take a closer look, using interventional clinical trials for medications as our guide.

The bridge to tomorrow’s medical advancements

Preclinical Phase: From research to breakthrough

Preclinical Phase: From research to breakthrough Let’s consider an example: imagine researchers discover a new and promising compound that shows potential to lower blood pressure during discovery.

Before this compound can be given to humans, it must undergo rigorous preclinical testing on animal models to assess its basic safety, effectiveness, and appropriate dosage levels. While also understanding how it interacts with biological systems and identify any potential risks.

Once preclinical research yields positive results and regulatory approval is granted, the investigational treatment enters clinical trials—a process divided into four distinct phases.

Let’s take a closer look at each phase and explore what it might be like to participate using this example as a guide.

Phase 1: Initial Safety and Dosage Evaluation

As a participant in Phase 1, you’ll be among the first humans to receive the investigational treatment. This phase typically involves a small group of fewer than 100 participants, often healthy volunteers or individuals with limited treatment options for their condition. Frequent medical exams and lab work may be part of your routine, and you’ll need to report any symptoms or side effects you notice.

The primary goals of Phase 1 are:

- Monitor participants closely for any side effects.

- Find the optimal dosage level that balances safety with potential efficacy.

- Observe how the treatment moves through and leaves the body.

On average, Phase 1 takes about two years to complete, and roughly 58% of treatments advance to the next phase.

Phase 2: Assessing Effectiveness

By joining Phase 2, you’ll help researchers learn whether the investigational treatment works for a specific disease or condition. This phase typically involves 100-500 participants who are randomly assigned to different groups. Some may receive the treatment, while others might receive a placebo or standard care to compare results. A placebo is an inactive substance that looks like the treatment but has no therapeutic effect, helping researchers measure the true impact of the investigational treatment.

Key objectives of Phase 2 include answering the following questions:

- Does the treatment improve the condition?

- Are there any additional side effects?

- What is the best dose for maximum efficacy with minimal side effects?

Phase 2 trials usually take about three years to complete, and approximately 31% of treatments successfully move on to Phase 3.

Phase 3: Confirming Benefits

By Phase 3, the trial includes a larger group of participants, typically ranging from 300 to 3,000 individuals with the condition being studied. This is the final stage before regulatory approval, designed to confirm that the treatment works and assess its benefits and risks compared to existing therapies.

Key aspects of Phase 3 include:

- Ensuring results are consistent across diverse populations.

- Often involves multiple treatment arms (groups of participants assigned to receive different treatments, such as the new therapy, a standard treatment, or a placebo) to evaluate how the new therapy compares to other options.

- The results from Phase 3 provide the critical evidence regulators need to decide if the treatment should be approved for public use.

Phase 3 typically takes about three years, and around 60% of treatments advance to regulatory submission, with the majority receiving approval.

Phase 4: Post-Approval Monitoring

Even after a treatment is approved, the evaluation doesn’t stop. Phase 4 trials, also known as post-marketing surveillance, involve thousands of participants and focus on:

- Monitoring how the treatment performs over extended periods.

- Identifying less common adverse effects that may not have appeared in earlier phases.

- Refining how the treatment is prescribed and used in real-world settings.

Phase 4 studies help ensure the treatment continues to provide safe and effective care while offering insights into potential improvements.

How Are Clinical Trials Designed?

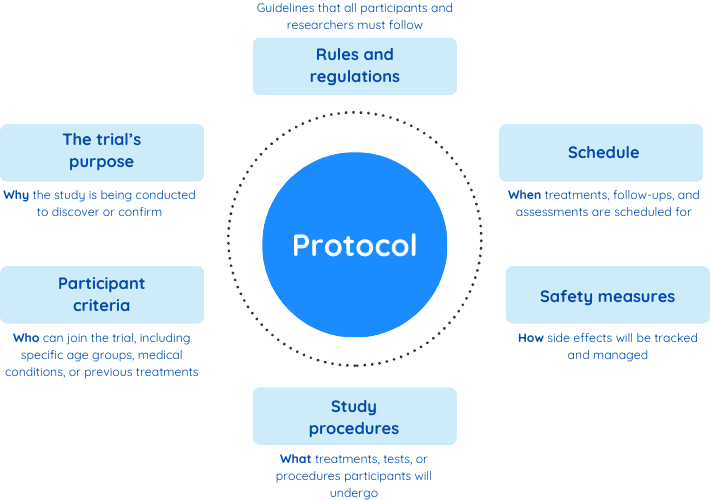

Clinical trials start with a carefully crafted plan called a protocol. Think of the protocol as the trial’s playbook, providing clear instructions on how the study will be conducted. It outlines every detail, from the trial’s purpose to how participants will be selected, treated, and monitored. This plan ensures the trial runs smoothly, protects participants, and produces reliable results.

Each phase of a clinical trial—whether it’s the early safety-focused stages or the larger, more comprehensive studies in later phases—follows its own specific protocol. For example, in Phase 1, the protocol emphasizes safety, detailing how the investigational treatment will be administered and how participants will be monitored for side effects. By the time a trial reaches Phase 3, the protocol expands to include how the treatment’s effectiveness will be compared to standard therapies or placebos across a larger, more diverse group of participants.

Here’s what a protocol typically includes:

The protocol also outlines three important elements to ensure fairness and accuracy:

Randomization

In clinical trials, participants are randomly assigned to different treatment groups, often referred to as “arms”, much like drawing names out of a hat. This process eliminates bias and ensures that the groups are balanced. For instance, one group may receive the investigational treatment, while another is given standard care or a placebo. Randomization is most used in Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials to ensure reliable comparisons.

Controlled Trials

Controlled trials use a comparison, or control group, to evaluate how well the new treatment works. This group might receive the standard treatment currently in use or a placebo. By comparing the results from both groups, researchers can determine whether the investigational treatment offers significant benefits. Controlled trials simply mean there is a control group for comparison, but participants may not necessarily be randomly assigned to groups as described above.

Blinding

In some trials, known as blinded trials, participants don’t know which treatment they are receiving to avoid influencing their expectations, participation or perceptions. In double-blind trials, both researchers and participants are unaware of who is receiving the treatment or the placebo. In single-blind trials participants don’t know whether they’re receiving the investigational treatment, standard care, or a placebo. This helps prevent their expectations from influencing the outcomes.

All clinical trials are eventually unblinded, either at the end of the study or when blinding is no longer needed. During this process, participants and researchers learn which treatment group each participant was assigned to.

How They Work Together

For example, a clinical trial can be:

- Controlled but not randomized: participants are assigned based on certain criteria rather than randomly.

- Randomized but not blinded: participants know which group they are in.

- Randomized and blinded: participants are randomly assigned, and neither they nor the researchers know who is in which group.

Conclusion

The detailed structure of clinical trials is crucial for producing trustworthy results. For participants, understanding the trial’s design provides reassurance and helps them feel informed and empowered throughout the process.

If you’re considering joining a trial, it’s essential to review the protocol and ask yourself, does this trial fit my needs and goals? understanding the design ensures you’re making the best decision for your health.

For a deeper dive, check out our article, Am I Eligible for a Clinical Trial?, where we explore how eligibility is determined as outlined in the trials protocol, what to expect during the screening process, and tips for finding the right trial